"Proper justice," as Daniele Archibugi explains, "is made in the tribunals, not outside them." Perhaps there was no choice, but it would have been "much more judicially satisfactory," if less immediately gratifying, "to have arrested bin Laden," and to give responsibility to the courts, "rather than to a commando" to judge and punish.

As human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson states, justice "requires a fair trial before an independent court." This was "a missed opportunity to prove to the world, and especially to the people currently rising up against tyrannies in Arab countries, that bin Laden was a false prophet with an inhuman and worthless cause."

Deborah Lipstadt, author of the recently published and highly regarded book The Eichman Trial, writes that it would be "tantalizing to imagine" bin Laden on trial -- "The United States’ biggest enemy would have been offered a striking illustration of American democracy: The rule of law applies to even the most nefarious defendants." While not "sorry that bin Laden was shot," she regrets "he never was shown the wonders of a democratic system of justice. It would have been the best response to the culture of death and hatred that this man represented."

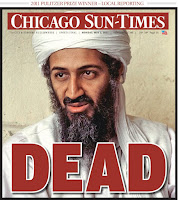

What should not be forgotten, as Karen Greenberg reminds us, is that the effect of bin Laden's reign of terror on the United States was to pervert our notion of justice: "Under the rubric of fighting terror, the United States rolled back its hallowed notions of civil liberties, its embrace of modernity, and even its reliance on its own courts. We delved into medieval-style torture, we reneged on our courts as a viable option for trying terrorists, and we blindly took aim at a religion, rather than its disaffected hijackers." And, thus, his killing was inevitable:

Bin Laden was an enemy so dreaded and so feared that his killing by military execution was the only possible end for a country that had given up so much of itself in his name. This was not a criminal, it was judged, that our courts, even after ten years, could handle. This was not an enemy whose fate the United States wanted to debate with the world and in the world's criminal courts. His killing put an end to innumerable conversations that would, arguably, have continued to confound nations and their citizens. In his death, as in his life, we followed his lead when it came to thinking about justice.It is, of course true, that a trial would have have been extremely difficult. Jeffrey Toobin lists some of the obvious hurdles. But, adhering to democratic principles, civil liberties and fundamental human rights when confronted with terror and violence is never easy. As Dean Rodricks points out, "American justice is complex and costly, tedious and cumbersome. But it is supposed to be the highest form of justice, closely watched by the whole world, including those rebelling this spring against the dictatorships of the Arab nations."

Putting bin Laden on trial rather than killing him would have constituted a powerful demonstration of our "freedoms," for which a former president claimed the terrorists hate us. Even with more disadvantages than advantages in pursuing a trial, as Daniele Archibugi asserts, "the fact that the most egregious criminal of this century was killed in an attempt to arrest him shows that we are still far from a global rule of law."

Perhaps, as Karen Greenberg concludes, "in sending bin Laden's body into the waters of the ocean, we should consider sending all that he represented to us to the bottom of the sea as well. Perhaps we could, in his absence, remember once again who we are, and begin to rebuild our confidence in ourselves – starting with our system of justice."

2 comments :

http://www.humanrights.ie/index.php/2011/05/04/the-doing-of-justice-to-osama-bin-laden/

What she said.

Thanks, Stephen. That is a pretty thoughtful take.

Post a Comment